Orlando, Florida, USA

Thursday 26 September 2024

Hurricane Helene is approaching the west side of Florida as a potentially catastrophic Category 3 hurricane, projected to bring up to 20 feet of storm surge to the Florida Big Bend, just south of the state capital, Tallahassee. While here in Orlando the situation is calm, and as of 6 p.m. ET on 09/26/2024, we’ve only experienced minor wind gusts and rain, the situation in northwest Florida will look (and surely feel) very different.

With rapid changes in our climate, extreme weather events, including Atlantic tropical storms and hurricanes, are showing shifts in their characteristics. Warmer ocean temperatures are mainly responsible for these changes, fueling more evaporation within the systems. This results in higher rainfall rates, larger hurricanes, and rapid intensification, which impacts the predictability of conditions at landfall (and beyond).

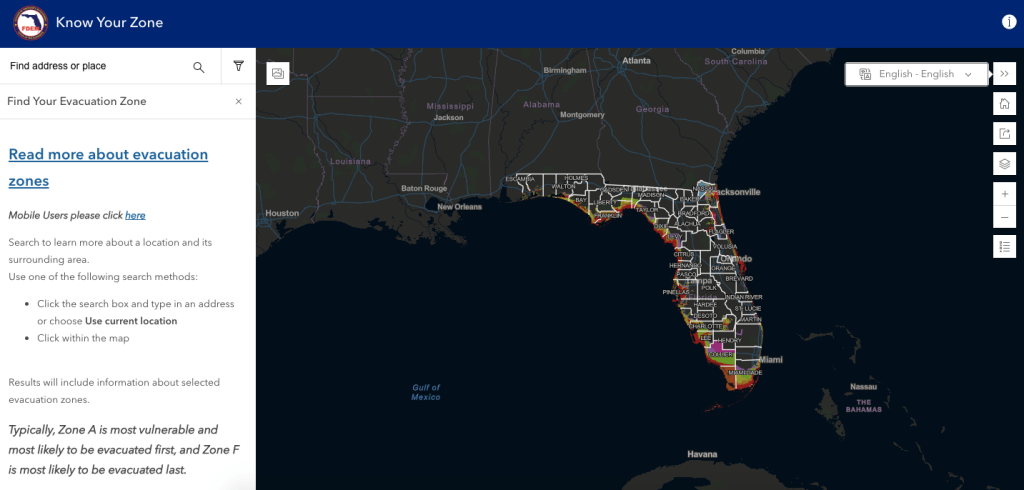

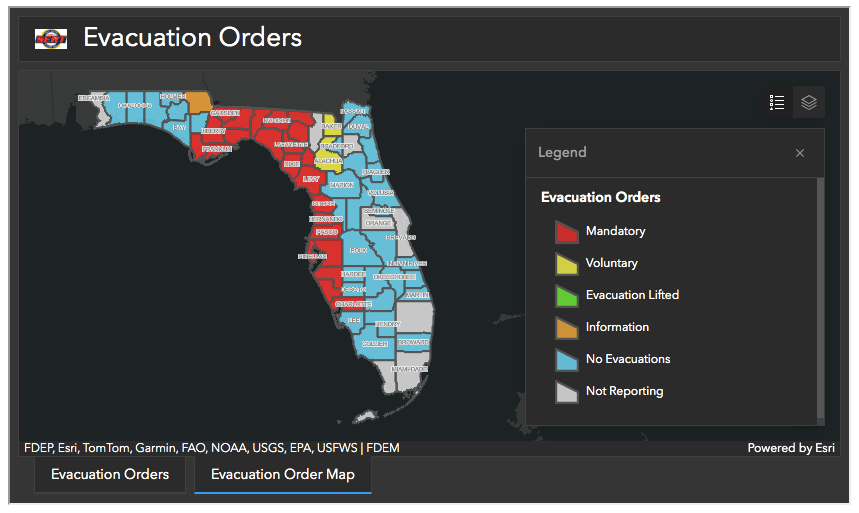

Hurricanes like Ian, which hit southwest Florida almost exactly two years ago (09/28/2022), are disasters from which we should learn several lessons. Hurricane Ian’s destruction in southwest Florida has been deemed one of the worst and costliest in U.S. history. Deadly storm surges of up to 15 feet devastated entire communities around Cayo Costa Island and Ft. Myers. The projected 20-foot storm surge from Hurricane Helene in the Florida Big Bend must be taken seriously. But are we doing so? Yes and no. Mandatory evacuation orders have been issued for most of the west Florida coast, far beyond the immediate coastline where Helene will make landfall. Upon the emergency declaration from Florida Governor, Ron DeSantis, affected counties issued mandatory evacuation orders for Zones A, B, and C, and other vulnerable areas, including low-lying regions and mobile homes.

However, a recurring issue I’ve heard in my capacity as both an emergency management scholar and a person living in Florida is that evacuation orders came too late. In fairness, Hurricane Helene’s projected impact on west Florida evolved rapidly and conditions changed quickly. Its intensification and organization dramatically changed within 24 hours, forcing decision-makers to act with limited time and ever-changing information. But two other concerns stand out, which might be of greater interest: “We didn’t learn from Hurricane Ian, and Helene looks so much alike” and “I couldn’t properly visualize the evacuation order on my phone” something I have heard over and over in the past couple of days while talking with both fellow professionals and dear friends. These issues are deeply interconnected and worth analyzing.

Hurricane Ian taught us that storm surges can be deadly; it can wipe out entire communities and transform landscapes. More importantly, it alters the post-disaster lives of people in affected areas. Prolonged, widespread power outages can severely affect communities, especially those with medically vulnerable individuals relying on electricity for at-home medical care. This was seen repeatedly in Puerto Rico, which I have studied for several years, particularly since Hurricane Maria in 2017. A related concern is the inability of medically vulnerable people to evacuate on short notice—especially given the less-than-24-hours timeframe between the issuance of evacuation orders and the arrival of dangerous weather conditions on Florida’s west coast. Even with provisions to help evacuate vulnerable populations, many individuals with chronic conditions struggle to evacuate safely, and may not qualify for external assistance.

From a scientific perspective, hurricanes—and their low atmospheric pressure caused by sudden drops in barometric pressure—can have severe health effects. Migraines are commonly reported, but low pressure also increases humidity, which can worsen respiratory conditions. Rapid drops in barometric pressure are linked to cardiovascular issues. People reported that their lingering cardiovascular condition worsened over the last 36 hours due to pressure changes, forcing them to delay their evacuation (despite being in a mandatory evacuation zone), to ensure they were fit to drive. These “gray” cases—where people don’t qualify for assistance but are too unwell to prepare properly—should be a focus for emergency management professionals and scholars alike.

On another note, Florida’s history with hurricanes sometimes makes evacuation orders go unheard. When I was investigating the emergency management capabilities of communities in the Florida Panhandle after Hurricane Michael in 2018, something unforgettable was a statement from one interviewee: “They are retirees who’ve lived in Florida for years. They either don’t trust the government or think this storm won’t affect them. The next day, they’re the ones we have to rescue, putting first responders’ lives at risk because they didn’t listen to evacuation orders.” This demonstrates how, often, lessons aren’t learned by both planners and the public.

It’s impossible to help, directly, every individual, but we can address many recurring issues. The key is risk communication. Hurricanes and extreme weather events will continue to occur, evolving in nature. Scientists are already working hard to identify these changes and to find ways to convey them clearly and manageably to emergency management professionals. But we need to break the cycle of ‘historical memory,’ as it affects individuals and communities’ ability to withstand the impact of hurricanes like Helene. Just because Category 1 hurricanes (and Helene is more than a Category 1 hurricane) haven’t been perceived as a threat in some parts of Florida for decades doesn’t mean that’s the case now. Hurricane Ian, for example, caused massive flooding and post-disaster disease outbreaks in Central Florida, despite weakening to a tropical storm/Category 1 by the time it reached the area. Why? Because the rapid changes in the climate are making storms wetter, just to name one shifting characteristic.

It’s time to work on an effective risk communication strategy to protect the people we aim to help, while also reaching those with less trust in the system. We can’t afford evacuation orders that are unreadable on mobile devices or that don’t address language barriers—especially in certain communities. Emergency managers will face growing challenges with these evolving storms. Time will often be insufficient, as was the case with Helene. Consistent communication strategies—accessible messaging, outreach, and education—are crucial. This is an ongoing effort, one that aims to save lives in these unprecedented times and to which I am dedicating my (professional) life.

Sara Belligoni

Featured Image Credits: NOAA/NESDIS/STAR

Sources

https://www.floridadisaster.org/disaster-updates/storm-updates/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2024/09/26/evacuations-hurricane-helene-florida/

https://www.tampabay.com/hurricane/2024/09/25/hurricane-helene-pinellas-county-evacuation/

https://weather.com/storms/hurricane/news/2024-09-26-hurricane-helene-live-updates-florida-georgia

https://www.nbcnews.com/news/weather/live-blog/storm-helene-live-updates-rcna172604

You must be logged in to post a comment.